On Afaf Zurayk: The Supremacy of Light & Silence

INTRODUCTION

When we enter Afaf Zurayk’s atelier and apartment in Hamra, which once was the vibrant heart of Beirut, we are immediately enveloped by a certain quality of silence and light, as if entering a sanctuary. We sit surrounded by the strong and nurturing presence of her paintings, in their white and evanescent colors and shapes. They emanate an aura that the artist herself exudes: a powerful sense of softness and embodiment. On the low table of her living room, Origami birds and colored pieces of wood from her series Driftwood contribute to this impression of softness and aliveness, an antidote to the tumultuous Lebanese environment outside. It is amidst this combination of turmoil, tenderness, and respite that Afaf Zurayk has produced most of her work, for which she was honored with the Juhayna Baddoura Award in 2017, a tribute to artists whose work has received less visibility than it deserves. When accepting the prize, the artist spoke about her “passionate engagement” with visual art. She said: “It is the place where I express my fervor and my emotions. It is the refuge that I have found for myself when the war erupted in Lebanon and turned our lives upside down. To escape terror and violence, I have started painting with even more fervor and poetry. And since 1978, I have entirely dedicated myself to art.”1 If Zurayk’s art could develop during the war and provide a means to resist it, it is because it is rooted in a Lebanon of “love and peaceful coexistence”2 she had grown up in. To stay connected to “grace”, a word she often uses, the artist recalled the “love and trust [she] experienced growing up among the pines and along the seashore [that] were not mirages but oases of infinite depth and richness that [she] still has the privilege of tapping into even now.”3

Zurayk’s work and the artist’s life is a testament to resilience and the power of art in the face of adversity. If Zurayk is not a traditionally engaged artist, she is no doubt a committed one, shaped by the upheavals and history of the Arab world. Even though her message is never direct – and this is perhaps its interest – her art is a resistance to the culture of silencing and of violence, a reminder of our shared humanity, in which she always found solace.

BECOMING AN ARTIST

Afaf Zurayk is one of the last figures of a generation of prominent Lebanese women artists who emerged in the 1960s–70s, when Beirut was an epicenter of art and creativity. Born in 1948, she came in touch with art at an early age, growing up in a highly cultured and modern family who encouraged her talent. When they first oriented Afaf towards painting, her parents viewed it as a means of channeling her energy. She was fortunate to have Helen Khal, a prominent Lebanese American artist, as was one of her tutors. Zurayk recalls having been totally enthralled by one of Helen’s paintings when she was nine years old, and that this was the moment she decided that she also “wanted to be in this place where [she] can show the transparency,”4 which she eventually did. The influence of Helen Khal on Zurayk was substantial; she looked up to her both as an artist and as an independent woman. Another important inspiration for Zurayk’s work, though she never knew her personally, was Lebanese artist Huguette Caland.

Afaf Zurayk was educated at Al Ahliya school, an institution famous for its post-modernist spirit, which very much aligned with the views of her father, the famous intellectual, historian, and academic, Constantine Zurayk, who was one of the pioneers of the Arab nationalist movement. Passionate about painting, Afaf trained in Fine Arts at the American University of Beirut and then studied Islamic arts at Harvard University in the United States (US). After graduating in 1972, she returned to Lebanon where she practiced her art and taught for a few years at Beirut University College (BUC), now the Lebanese American University.5 At BUC, Afaf met Dorothy Salhab Kazemi, the renowned ceramist who was also a teacher at BUC, and they became close friends. Together, they exchanged views about art, philosophy, poetry, and life. Her friendship with Dorothy marked the artist’s artistic and personal journey. In those years, just before the outbreak of war in 1975, Beirut was booming. The violence that followed was a definitive turning point for Zurayk, who said she felt that “the carpet was taken from under [her] feet.”6 Despite this, and perhaps because of it, Zurayk decided in 1976 to focus on her artistic practice. She recalls: “The only thing I could ground myself in was my art.”7

“RESOUNDING SOUND OF SILENCE”: ZURAYK’S ART

According to Zurayk, her art helped her cope with violence, darkness, and the existential questions that living in a volatile and harsh environment raises. “My art has made me face the question of evil or the combination of beauty and violence,” she says.8 Indeed, even in her dark paintings, there is always a shaft of light. “The focus on darkness is misleading,” the artist observes, while recognizing that her “early paintings were very dark and troubled.”9 Now, with a more serene and mature vision, she seems to have come to terms with the duality of light and darkness. “The reason why you are here is not to dwell on the darkness, but to embrace it, to appreciate and be in touch with the light. Being born is to face these things,” she explains.10 According to her, having lived through the Civil War in Lebanon does not make her experience of darkness unique. “The human experience in itself is dark. It’s about the chaos of living, the violence that is in life. I experienced it in the civil war; others experience it in the US, for instance, in another fashion. I so happen to have experienced the war in Lebanon, in Syria, in Palestine.”11 She realized this common experience of suffering when she lived in the US, after having fled the war in Lebanon in 1983, following the Israeli invasion of Beirut. “Being away from home there, I knew I had to be very creative about life. The US is tough, it offered me a lot. Everything was permitted there at that time; it pushes you to reinvent the wheel every time you make a new step,” she remembers.12

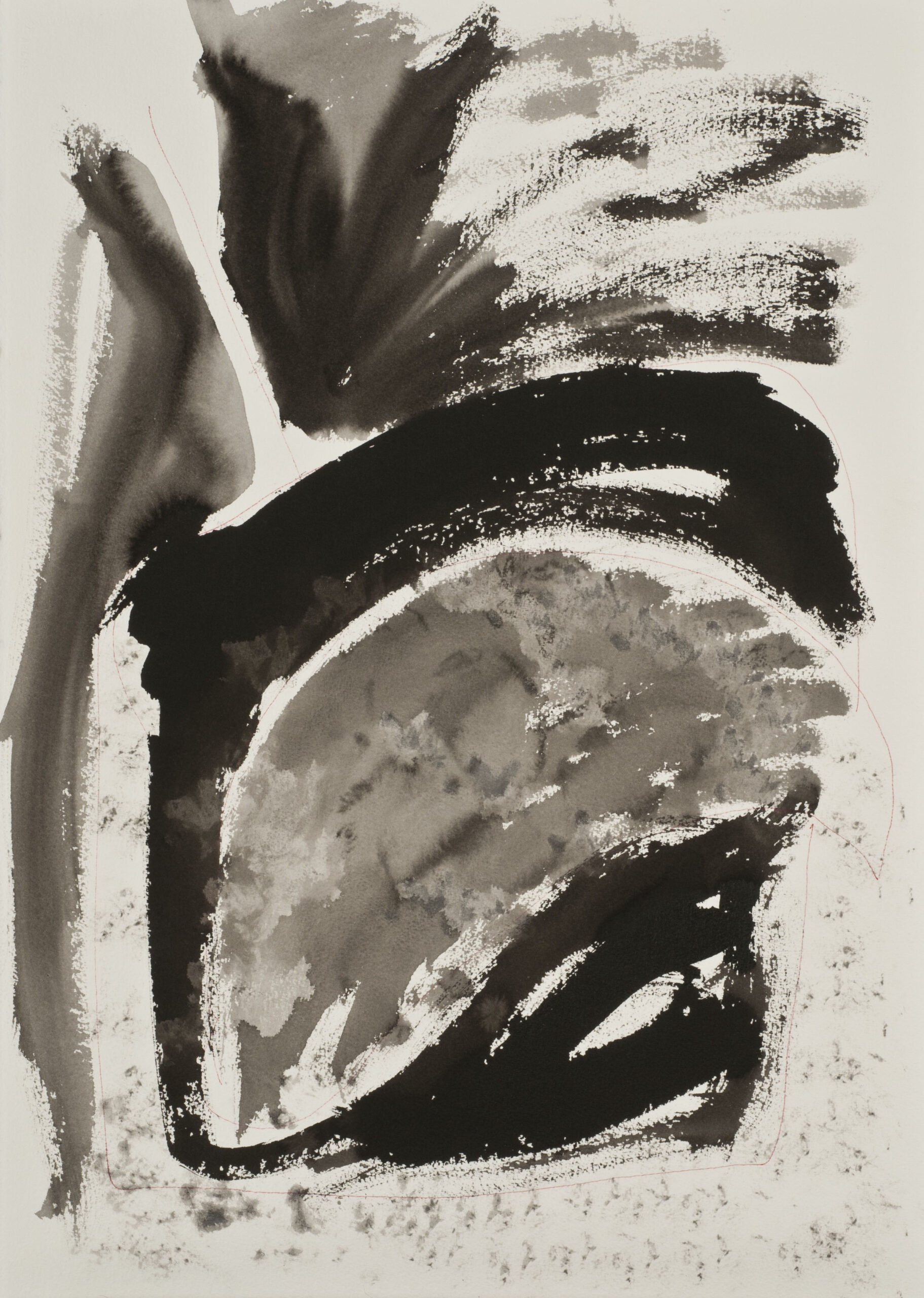

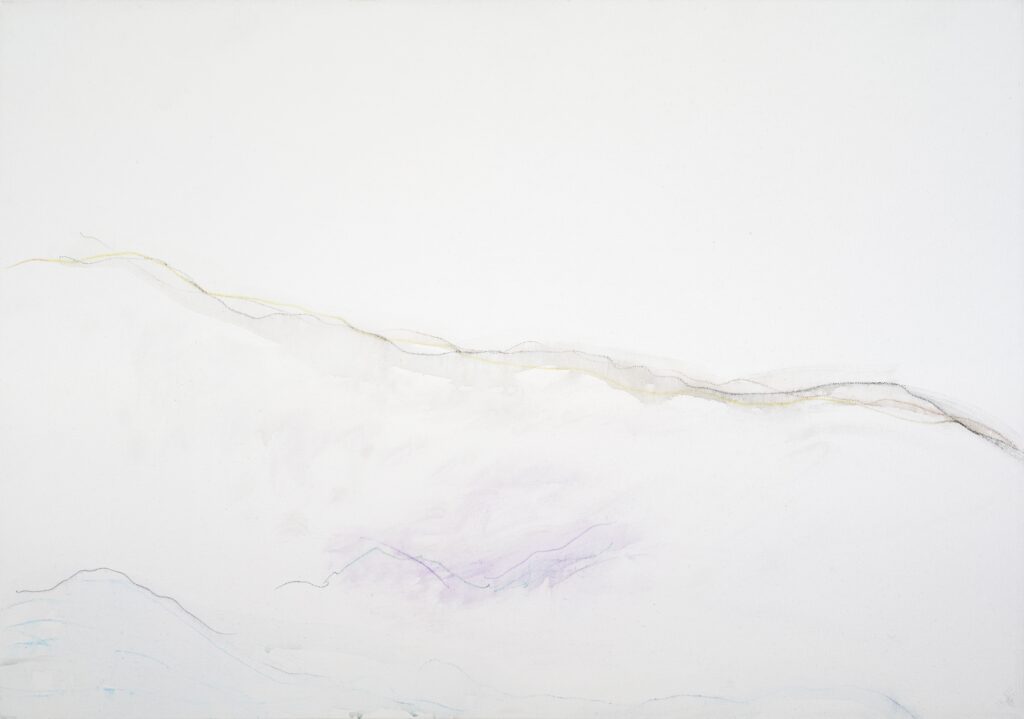

Zurayk’s art is subtle and all about abstraction, and her creativity is, paradoxically for a visual artist, not as much about seeing as it is about listening. According to her, the impulse driving her work is listening to “the resounding sound of silence,”13 which triggers in her an initial gesture that then engenders what she calls a choreography of movement. In the past, she often used to listen to music – notably Schubert – before painting, allowing the music to inspire her. Nowadays, however, she more often listens to silence than to music in an attempt to seize the intangible. Sylvia Agemian, Zurayk’s friend and curator of the retrospective exhibition Return Journeys, called her “the painter of the intangible.”14 Zurayk is not direct in her art; she captures the subtle intricacies, touches, and motions of the human experience in her painting, sculpture, and writing, rather than something clearly definable. All her art emanates from her profound inner life, with her emotions as her compass. Wholly feminine in this respect, though discrete, she attests that her life, her emotions, and her art are all intertwined. This is a dialectic dynamic: “I don’t separate art from living. My life is my art and vice versa”, she says.15

If her work is more about a texture and a feeling than clearly about content, there are nevertheless a few major recurring themes and subjects: inner exploration, self-questioning, the entanglement of personal and collective journeys, the call of nature and of life in its natural abundance; that of water, of forests, of the sky and their symbolism of continuous regeneration, femininity, and womanhood; the multiplicity of worlds, possibilities, and layers; spirituality and a philosophical quest to address the questions of violence, of suffering, and of forgiveness, including of oneself. In this spiritual realm, Zurayk subtly evokes the figure of Christ in her work, such as in Everyman, a piece she painted as part of a series after her sister passed away.

These themes are reflected in the titles of her exhibitions: Light Enters (2025) in Paris together with Amy Tod man; Beirut Octet (2023); White (2021); Shifting Lights (2017), in collaboration with photographer Noël Nasr and architect Rami Saab in the iconic museum Beit Beirut; …and morning drew softly (2013), Scripted on water (2012), and A day in the life of a pomegranate (2013), the latter two together with Cornelia Krafft. Moreover, Zurayk’s piece Driftwood, made of wood debris collected on the seashore in Maryland, accompanied many of her exhibitions. As these examples illustrate, Afaf Zurayk has chosen to focus on light, fluidity, and the ethereal, which has become her signature style. With this prolific production, the artist, though reserved and low profile, has been exhibited by major Lebanese gallerists such as Jeanine Rubeiz and Saleh Barakat. Outside of Lebanon, she has participated in collective exhibitions, notably in the US where she lived for around twenty years after leaving Lebanon during the war. Her artwork can also be found in the permanent collections of the British Museum in London, the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, the Sursock Museum in Beirut, and Darat Al Funun in Amman.

ZURAYK’S CREATIVE PROCESS

Zurayk’s creative process resonates with the themes of the human experience and the universal laws she seeks to convey through her art in all their complexity and richness. When she taught, she invited her students to take the less traveled road, as she does when creating art: taking time, listening to one self, accumulating sensorial experiences, reading, contemplating, reflecting, and then interiorizing and channeling the fruit of this process into the gestures of the hand. “My fingers tell me, they start tingling. I don’t know before I start painting what I will paint. It starts with a simple idea, then the art happens […] I am in control of everything, yet fully surrendering to the canvas,” she reveals.16 With the years, she says, she has become increasingly at ease with the subtlety of this process: “being extinct and alive at the same time. You are doing and not doing… It is a way of being which has become very pronounced in my late years.”17

To navigate this liminality, the artist constantly observes the light in her flat and wakes up at dawn every day to contemplate the shifting light. In this process, she he has learned to tame the darkness: “When there was no electricity, the darkness taught me a lot about the shape of my skin, about feeling things. I am grateful to the gift of darkness of the war. You can understand your body and activate your imagination through the blackness of the room.”18

The medium she uses depends on her subject and the inspiration of the moment. Whether with oil, watercolor, crayon, charcoal or ink, what she seeks is the purity of the line which creates space and tonality that in turn evoke emotion. She describes this process as a movement: “Things come in and out.”19 It is this movement that the artist aims to represent, notably through the technique of layering. Using only a few colors, she creates layers, allowing tonalities to dilute in delicate nuances.

When she was younger, Zurayk was inspired by the psychiatrist Carl Jung, whose views on the human experience she relates to, and the Dutch painter Rembrandt because of his mastery of the the chiaroscuro technique that creates his characteristic contrast of light and darkness, which fascinated her, especially in his portraits. In her own portraits, Zurayk paints more of a presence, an inner reality, or layers of inner realities, than precise figures and faces. This was the case for instance in her exhibition Shifting Lights, in which her art represented scars in the soul rather than physical wounds. This is also visible in her sculpture series My Father. Reflections, an homage to her late father, which was photographed by artist and photographer Noël Nasr.

A MULTIDISCIPLINARY POET

Afaf Zurayk’s art is multidisciplinary, and she enjoys the liberty to play with different artforms and travel from one to the other. In the same way she is not attached to a specific artform, Zurayk is not concerned by labels or categories. One of her media of expression is poetry. Her writing and her poetry are an intrinsic part of her artistic journey. “I write a poem, and something triggers the painting,” she says. “It is not a direct relation. Sometimes writing and painting happen together. I have no discipline. I do it when I feel it, I write when I hear the words. There is no preceding intentionality. You let yourself be open and then channel whatever is inspiring you.”20

Often her poetry is published alongside her painting and through her writing, the artist documents her artistic process. The catalogs, monographs, and books usually published in parallel to her artwork are themselves also artistic pieces. Over time, writing has become as important as painting for her. She thinks she “understood a lot through being both the artist and the observer of [her] art. I let go and allow myself the freedom to paint whatever comes to mind and then observe what it is telling me and how I must live my life thereon. It informs me about myself; it tells me more about myself than I can tell myself.”21

Her publications are also a means to ensure her legacy for future generations, with whom she loves to communicate. While she lives quietly in her Hamra apartment, which is her oasis, she affirms that no one, including artists, is an island. Despite having stopped teaching at university, she has open-heartedly welcomed collaborations with younger artists, notably Noël Nasr and Rami Saab who have become very dear to her and with whom she says she has “a very special, deep friendship.”22 She has also collaborated twice with Cornelia Krafft, a German artist residing in Lebanon and in 2025 had an exhibition in the 15 Beautreillis space in Paris, collaborating with Amy Todman, a young Scottish artist also living in Beirut. The relationships Zurayk has with her curators are also important to her, especially the one she has with Saleh Barakat, the established visionary gallerist who promotes Middle Eastern art. Zurayk’s latest series she is working on was inspired by a conversation between her and the gallerist. “He saw something that I hadn’t seen in my work. I took the time to listen to him; he sparked something and then I began. Such conversations are important, as is every conversation with a good friend, especially those who are artists. They open gates for you.”23

CONCLUSION

Looking back at a life of prolific artistic production, Zurayk considers her work and her journey a part of a wider human experience and community. Hence, the artist who situates herself at the confluence of generations and geographies, sees her role as a “link in the chain of humanity, in this cycle of life and death where man intervenes as a medium” and where “the artistic act completes that of creation.”24 In this transmission chain, she is particularly grateful to her parents, two refined, self-made individuals who always looked to the future, despite difficulties, who nurtured her with love and sensitivity, and imparted strong values of integrity, authenticity, and intellectual honesty. It is those foundations that gave Afaf the power to pursue her calling and to cultivate faith and grace in her work. She invites Arab women artists in particular to connect to this faith, “to just believe in themselves, follow what they think is right and not compromise; keep their vision where they want it to be.”25 Zurayk says: “I see my art as a garden without a fence. In the past, I built fences that bound my return, my search, in time and in space. Today, I feel my garden opening, becoming limitless and free, having been watered by endless journeys of exile and of communion; of love and of separation; of milk and of merging mirrors. I only wish that my garden is deep enough and expansive enough to contain you. For we are each other’s mirror. And our birth grows out of our joint reflection. My hope is that these reflections form the roots for more growth and more love. Despite all.”26

The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author and do not represent Fiker Institute. To access the endnotes, download the full report.

This essay is part of Written Portraits: Arab Women, Art, & History, a series that focuses on the lives and works of Arab female artists, authored by Arab female researchers in collaboration with the Barjeel Art Foundation.