Nation Branding in the Gulf

For much of the 20th century, Arab oil-exporting states were defined as rentier economies, where a small percentage of the population – often just 2-3% – was involved in producing wealth that accounted for up to 80% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).1 According to modern interpretations of Adam Smith’s rentier theory, state revenue in such economies accrues directly from natural resources rather than broad-based production. Since the early 2000s, globalization and economic integration have compelled Gulf economies to reassess their dependence on hydrocarbons. To remain globally competitive, the region has had to reconfigure its economic foundations.

Today, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), established as a regional bloc in 1981, is undergoing one of the most significant economic transformations in its history. GCC member states are facing volatility in hydrocarbon markets, mounting geopolitical tensions, innovation in alternative energies, and the need for sustainable development. As GCC member states accelerate their efforts to diversify beyond hydrocarbons, the role of nation branding – the projection of a cohesive national identity to global audiences – has emerged as a critical, yet underexplored, instrument of economic strategy.

While centered on infrastructure, fiscal reform, and human capital investment, economic diversification efforts increasingly depend on long-term strategic communication tools to shape international perceptions. Among these tools, nation branding has become a vital pillar of economic diplomacy. Despite growing investment in branding campaigns and soft power initiatives, empirical analysis of their effectiveness in advancing non-hydrocarbon economic growth remains limited. This Policy Brief examines how nation branding is being used across the six GCC states to attract foreign direct investments (FDI), support sectoral growth, and reposition the $2.3 trillion regional economy as future-oriented.

WHAT IS NATION BRANDING AND WHY DOES IT MATTER FOR THE GULF?

Nation branding is the strategy with which countries craft and communicate a distinct identity to global audiences. Unlike public diplomacy, which centers on state-to-state engagement, nation branding is market-facing, i.e. it interacts with a much larger and more diverse audience. Nation branding merges elements of soft power, marketing, and policy alignment to position countries in a competitive global economy. A nation’s brand, a term coined by Simon Anholt, is “the sum of people’s perceptions of a country across multiple dimensions,”2 including governance, exports, culture, tourism, investment potential, and human capital. In this sense, a nation’s brand can be viewed as both an asset and a liability, capable of attracting or repelling global engagement.

While nation branding is a recent addition to the International Relations literature, many known philosophers and researchers have studied different aspects of how nations are perceived. Noam Chomsky’s work on propaganda provides an interesting perspective of the “perception of the nation”, which he views as complex and multifaceted.3 Chomsky critiques the ways in which national identity is constructed and manipulated. He sees the nation as a social construct, rather than a naturally existing entity, and examines how dominant narratives and propaganda systems shape public perception of national identity and purpose. However, the construction of a nation’s brand is also heavily impacted by its socio-cultural influence, hence the existence of institutions like the British Council and the Alliance Française. Crucially, nation branding is not about logos or slogans, but about reputation.

While economic diversification has traditionally focused on infrastructure, regulation, and financial incentives, this brief argues that branding, when aligned with strategic economic goals, can enhance the visibility, credibility, and competitiveness of non-hydrocarbon sectors. Nation branding supports diversification indirectly by shaping investor perceptions, amplifying economic reforms, and creating cohesive narratives around important GCC sectors such as tourism, renewable energy, logistics, and fintech. Nation branding, however, is not a substitute for structural reform. It is a complementary enabler that is most effective when embedded in broader national strategies, coordinated across state institutions, and backed by data, performance metrics, and a credible long-term vision.

For GCC member states, the significance of nation branding is especially relevant for several reasons. Firstly, reputation is an important gateway for investment: All six GCC states depend on FDI to diversify. Investor decisions are increasingly influenced not only by macroeconomic indicators but also by perceptions of political stability, ease of doing business, regulatory credibility, and cultural openness. Secondly, the Gulf region is now competing globally for the same pool of investors and skilled migrants. A credible brand identity provides a competitive edge in the global race for skilled labor and capital. Thirdly, branding is not just about image, it can be central to states’ economic strategies. When integrated with industrial policy, nation branding can become a platform for structural transformation, targeting key sectors, aligning with national visions, and enhancing global positioning. However, as subsequent sections will show, branding efforts across the region remain uneven, fragmented, and insufficiently evaluated.

MAPPING THE NATION BRANDING LANDSCAPE IN THE GCC: A COMPARATIVE OVERVIEW

Economic diversification is a strategic imperative for the GCC. In 2023, hydrocarbon revenues still accounted for a weighted average of over 60% of total government income across the region. While national strategies vary, each country has launched initiatives targeting non-hydrocarbon growth.

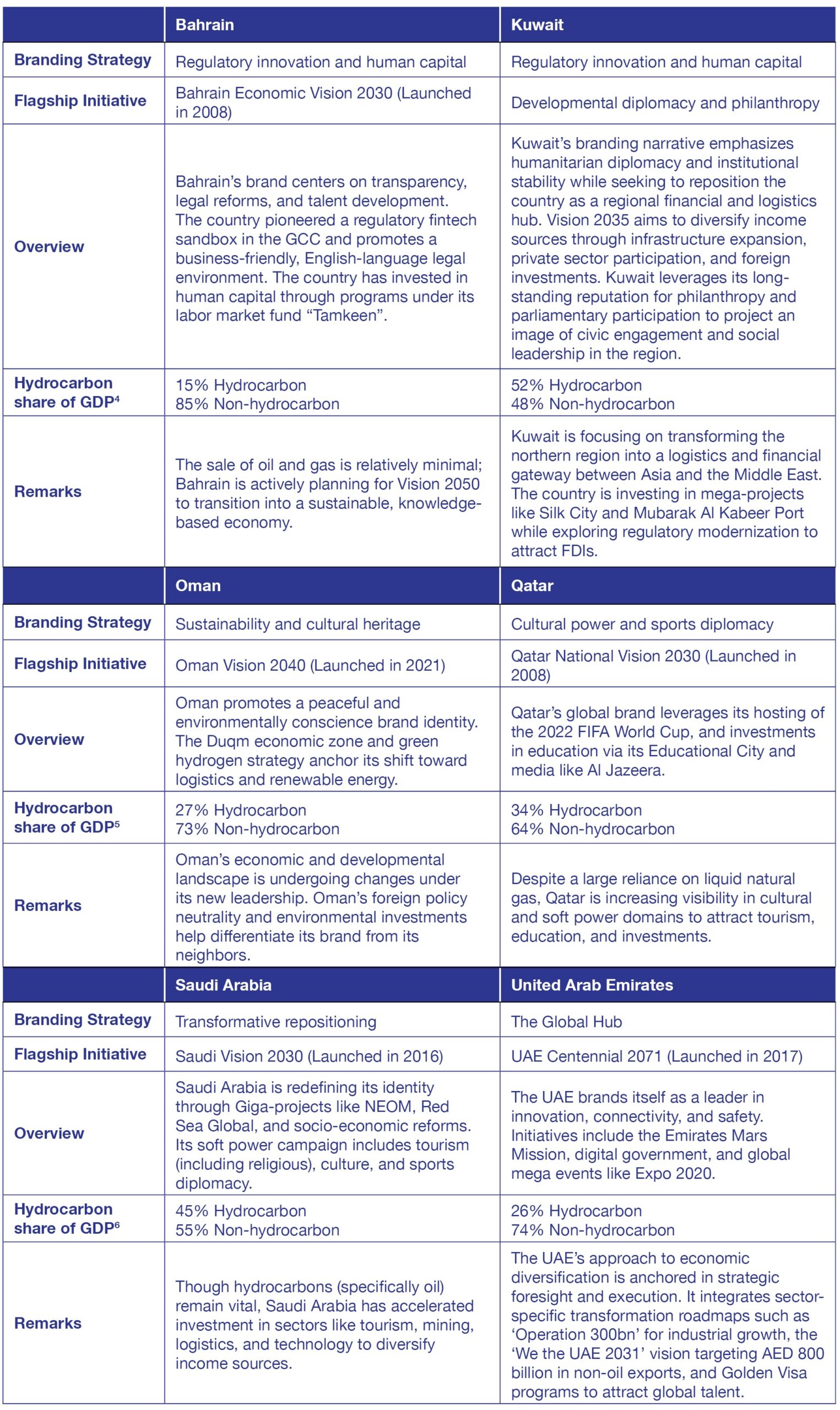

GCC Nation Branding Matrix:

GCC countries’ economic diversification visions rely on branding for narrative control and investor communication. For example, Bahrain has positioned itself as a business-friendly hub, emphasizing fintech and regulatory openness. Kuwait, by contrast, has anchored its branding around Vision 2035 ‘New Kuwait’, which seeks to transform the country into a financial and commercial hub through private sector growth, infrastructure investment, and governance reform; however, its impact remains limited due to slower reform implementation. Oman’s narrative is increasingly tied to renewable energy, especially hydrogen, while Qatar has leaned heavily on mega-events like the FIFA World Cup and its role as an international mediator. Saudi Arabia has placed futuristic projects such as NEOM and Vision 2030 at the heart of its global image, while the UAE continues to project itself as a global hub for innovation, technology and space exploration. Taken together, these approaches highlight both the diversity of strategies and the uneven success of execution, with countries like the UAE and Bahrain showing stronger alignment between branding and economic reform, while others risk over-relying on symbolic projects or events. Yet, campaigns across the GCC are often fragmented, overly dependent on mega-events, and weakly tied to long-term strategies. In a world of mobile capital and increased geopolitical volatility, perception influences risk. GCC states must therefore offer not only compelling narratives, but also credible signals of economic transformation.

BRANDING AND DIVERSIFICATION: EVIDENCE OF IMPACT

In the GCC, branding strategies are increasingly deployed to attract investment, promote sectoral development, and reposition economies within global value chains.

FDI flows and branding campaigns:

The data suggests that the UAE and Bahrain have outperformed other GCC countries in attracting FDIs relative to the size of their economies. This success is not only the result of favorable regulatory environments but also reflects coherent nation-branding strategies. Both countries have consistently projected themselves as open, business-friendly hubs, which appear to correlate with investor confidence and higher FDI-to-GDP ratios.

By contrast, Kuwait and Qatar show weaker results, with FDI inflows constituting a small share of GDP despite their financial capacity and international visibility. In Kuwait’s case, the limited traction of Vision 2035 reflects the gap between branding ambitions and the pace of domestic reforms. Qatar’s global visibility through the FIFA World Cup and its mediation diplomacy has enhanced its soft power, yet this is not translated into significant investment attraction in non-hydrocarbon sectors, suggesting that mega-events alone are insufficient without sustained reform alignment.

Competitiveness and diversification indices further underscore this pattern. The UAE consistently ranks higher on both competitiveness and diversification, reinforcing the argument that nation branding is most effective when combined with institutional reforms, regulatory readiness, and policy follow-through. Oman, Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, show notable improvements in economic diversification scores between 2000 and 2023,9 indicating that branding efforts tied to new industrial and energy strategies may be beginning to yield results.

At the same time, the evidence discussed should be interpreted cautiously. Nation branding is difficult to isolate as a causal factor: high FDI inflows and competitiveness rankings also reflect structural reform, global market dynamics, and geopolitical considerations. Branding acts more as a facilitator, amplifying reforms when credibility is strong and weakening perceptions when reforms lag behind. This suggests that while nation branding has measurable correlations with diversification, its effectiveness ultimately depends on whether narratives are matched by domestic policy delivery.

COMPARATIVE LESSONS: BENCHMARKING GLOBAL NATION BRANDING MODELS

Every state in the world is associated with an image, without necessarily having existing institutions managing day-to-day operations of nation brand management. To refine their branding strategies, GCC states can draw lessons from countries that have successfully linked national image to economic transformation.

Singapore: Competence and Predictability

Singapore’s transformation from a trading port to a global innovation hub is underpinned by a nation brand of efficiency, trustworthiness, and strategic centrality. Its brand communicates political stability, legal transparency, and attracts highly skilled labor, which are qualities that appeal to risk-averse investors. This is coupled with strategic initiatives like Singapore’s Economic Development Board which offers centralized services for businesses and investors. Moreover, on a governmental level, Singapore has implemented public diplomacy initiatives, such as “Smart Nation Singapore”, which align branding with national innovation policies.

Bahrain and the UAE, in particular, can draw on Singapore’s model. Both countries seek to project business readiness and governance maturity, positioning themselves as gateways between East and West. Like Singapore, they are relatively small in size and population but aim to punch above their weight by leveraging regulatory ability and strategic location.

South Korea: Cultural and Technological Soft Power

South Korea’s nation brand is inseparable from its cultural exports (e.g. K-pop and film industry) and technological dominance (e.g. Samsung and Hyundai). These elements position it as a high value, forward-looking, and innovative economy. South Korea’s cultural exports have had a major impact on reinforcing its nation brand, what is often referred to as the “K-brand effect”. Interestingly, South Korea’s Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA) plays a dual role in nation branding and attracting FDI, as it is responsible for policy implementation as well as image management.

Given their existing investments in culture and sports, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE could integrate insights from South Korea’s nation branding policies. By integrating soft power investments within a clear economic narrative they could replicate aspects of South Korea’s success, for example by linking mega-events and cultural exports to tourism, FDI attraction, and creative industries. However, cultural resonance is context dependent. On the one hand, like other Arab and Muslim-majority countries, GCC states have to navigate international stigmas and Islamophobia. On the other, K-pop became globally influential through grassroots fan networks,10 which cannot be engineered from the top down in the same way. GCC states will need to balance state-led initiatives with organic cultural participation to achieve credibility.

Switzerland: Branding Trust, Quality, and Stability

Switzerland’s branding success lies in projecting neutrality, high living standards, and financial expertise, all while maintaining a modest geographic and demographic footprint. Its long-term brand consistency has built resilience regardless of political or economic cycles. Switzerland leverages its neutrality not only through its foreign policy but also by positioning itself as one of the main global multilateral hubs, hosting key international organizations in Geneva.

Oman, Qatar, and Kuwait could adapt elements of the Swiss model by emphasizing their foreign policy neutrality and positioning themselves as diplomatic mediators within a turbulent region. This approach could allow them to brand themselves as an ‘oasis of stability’ and attract investments that seek predictability amid volatility in the region. However, limitations naturally exist; unlike Switzerland, these countries are heavily embedded in regional politics, meaning their neutrality may not be perceived as absolute. Strategic communications would therefore need to be carefully calibrated to highlight stability without overpromising insulation from conflict.

POLICY ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Across the GCC, nation branding remains disjointed and inconsistently tied to economic diversification objectives. Ministries of tourism, investment, and culture operate in silos, and SWFs, despite their global outreach, are underused as brand assets. Moreover, few states measure the impact of branding on investor behavior or economic outcomes.

There is also limited research on how the Gulf is perceived as a collective entity. Unlike other regional blocs around the world, the Arabian Gulf is highly integrated in terms of language, cultural norms, social traits, and other important considerations. Despite Western influence and century-old ties in the region,11 few studies explore how GCC states collectively navigate external perceptions.

Tangible outcomes are evident in countries where branding is embedded with coherent national strategies and linked to reorganization, regulation, or deregulation. This is most visible in the UAE, where branding as a hub for innovation and investment has been matched by regulatory reforms such as free trade zones, visa liberalization, and fintech regulation that reinforce the credibility of its narrative. Bahrain offers another good example: its “Business-friendly Bahrain” campaign is supported by an open regulatory sandbox for fintech, helping it attract proportionally high levels of FDI relative to its GDP. By contrast, Kuwait’s Vision 2035 has struggled to gain traction, as branding initiatives have not been accompanied by consistent policy reforms, highlighting the risks of a disconnect between narrative and implementation. These examples demonstrate that branding amplifies diversification only when backed by structural change, measurable reforms, and credible delivery.

Against this backdrop, this brief identifies several key challenges and opportunities for GCC countries to further leverage nation branding efforts to support their economic diversification.

Key gaps identified:

1. Geopolitical volatility and brand fragility

While many Gulf states position themselves as mediators, bridge builders, and multilateral hubs, ongoing regional tensions can undermine these efforts and counter nation branding campaigns. This geopolitical instability is one of the most important threats to the attractiveness of GCC states for foreign investments.

2. Lack of performance metrics

Evaluations of current branding initiatives often focus on output like events or social media impressions, rather than outcomes like investor sentiment, sectoral FDI monitoring, or changes in global perception. This is problematic because output measures visibility, not impact: a country can host world-class events or attract online attention without meaningfully shifting investor confidence or advancing diversification goals. Without outcome-based metrics, policymakers risk mistaking short-term publicity for long-term economic transformation.

3. Institutional fragmentation

Branding responsibilities are dispersed across tourism boards, investment agencies, and ministries, without a central coordinating body, leading to inconsistent messaging, missed synergies, and opportunity cost.

4. Underutilization of SWFs

Although SWFs hold significant global assets and visibility, they are rarely leveraged as tools for projecting national identity or credibility in international markets.

Strategic Recommendations:

1. Explore regional coordination

GCC states should consider developing a shared GCC brand identity for key sectors specific to the Arabian Gulf. Given the benefits of close socio-economic integration between all six member states, a unified message can amplify the GCC’s collective influence and reduce intra-Gulf competition for the same investment pool. Having a solid strategy on this front would also aid strategic decision-making, reducing margins of opportunity costs. The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is a major example of such strategic regional cooperation.

2. Establish nation-branding councils

Within each state, the government should create dedicated bodies to oversee branding strategies across ministries, ensuring consistency between domestic reform agendas and external messaging.

3. Incorporate geopolitical positioning into brand strategy

Gulf states should proactively frame their diplomatic roles, efforts, and leadership for a peaceful, secure region in a transparent and data-driven narrative. This means owning complexity, while promoting stability and vision in a volatile neighborhood.

4. Leverage SWFs as global brand ambassadors

Gulf states should position SWFs not just as financial vehicles, but as soft power tools by partnering with strategic sectors abroad that align with national brand values.

5. Develop brand-performance dashboards

Governments should introduce data tools to monitor how branding efforts correlate with perception indices, FDI inflows, tourism metrics, and sectoral performance. This would allow policymakers to iterate based on quantitative evidence.

6. Ensure message credibility through policy alignment

Nation branding is only effective when it reflects consistent policies. For the GCC, this means assessing how international investors, policymakers, and key partners perceive the region, and then aligning messaging with domestic progress and foreign policy behavior. Overpromising brand narratives can undermine credibility, for example, when they promote openness while restrictive regulations persist. Conversely, when reforms and diplomacy are clearly communicated and delivered, branding acts as a multiplier of trust.

CONCLUSION

Nation branding is emerging as a strategic enabler of economic diversification in the GCC, but its effectiveness depends on credibility, institutional coherence, and alignment with reform. While the region has made visible strides in projecting new images to global audiences, the outcomes remain uneven because branding is too often detached from policy delivery. Examples of nation branding efforts worldwide demonstrate that nation branding can accelerate investment, strengthen competitiveness, and reinforce reform, but only when it is grounded in tangible domestic change. Moving forward, GCC states must invest in outcome-based metrics, coordinate branding through central institutions, and ensure that collective external narratives accurately reflect policy realities. If implemented well, nation branding can act as a multiplier of reform and help position the Gulf as a competitive, future oriented region in a post-oil world.

The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author, and do not represent Fiker Institute. To access the endnotes and the hyperlinks in the tables, download the PDF.